Antiquity

When writing systems were invented in ancient civilizations, nearly everything that could be written upon—stone, clay, tree bark, metal sheets—was used for writing. Alphabetic writing emerged in Egypt around 1800 BC. At first the words were not separated from each other (scripta continua) and there was no punctuation. Texts were written from right to left, left to right, and even so that alternate lines read in opposite directions. The technical term for this type of writing is 'boustrophedon,' which means literally 'ox-turning' for the way a farmer drives an ox to plough his fields.

Scroll

Papyrus, a thick paper-like material made by weaving the stems of the papyrus plant, then pounding the woven sheet with a hammer-like tool, was used for writing in Ancient Egypt, perhaps as early as the First Dynasty, although the first evidence is from the account books of King Neferirkare Kakai of the Fifth Dynasty (about 2400 BC).[6] Papyrus sheets were glued together to form a scroll. Tree bark such as lime (Latin liber, from there also library) and other materials were also used.[7]

According to Herodotus (History 5:58), the Phoenicians brought writing and papyrus to Greece around the tenth or ninth century BC. The Greek word for papyrus as writing material (biblion) and book (biblos) come from the Phoenician port town Byblos, through which papyrus was exported to Greece.[8] From Greeks we have also the word tome (Greek: τόμος) which originally meant a slice or piece and from there it became to denote "a roll of papyrus". Tomus was used by the Latins with exactly the same meaning as volumen (see also below the explanation by Isidore of Seville).

Whether made from papyrus, parchment, or paper in East Asia, scrolls were the dominant form of book in the Hellenistic, Roman, Chinese and Hebrew cultures. The more modern codex book format form took over the Roman world by late antiquity, but the scroll format persisted much longer in Asia.

Codex

Papyrus scrolls were still dominant in the first century AD, as witnessed by the findings in Pompeii. The first written mention of the codex as a form of book is from Martial, in his Apophoreta CLXXXIV at the end of the century, where he praises its compactness. However the codex never gained much popularity in the pagan Hellenistic world, and only within the Christian community did it gain widespread use.[9] This change happened gradually during the third and fourth centuries, and the reasons for adopting the codex form of the book are several: the format is more economical, as both sides of the writing material can be used; and it is portable, searchable, and easy to conceal. The Christian authors may also have wanted to distinguish their writings from the pagan texts written on scrolls.

Wax tablets were the normal writing material in schools, in accounting, and for taking notes. They had the advantage of being reusable: the wax could be melted, and reformed into a blank. The custom of binding several wax tablets together (Roman pugillares) is a possible precursor for modern books (i.e. codex).[10]The etymology of the word codex (block of wood) also suggests that it may have developed from wooden wax tablets.[11]

In the 5th century, Isidore of Seville explained the relation between codex, book and scroll in his Etymologiae (VI.13): "A codex is composed of many books; a book is of one scroll. It is called codex by way of metaphor from the trunks (codex) of trees or vines, as if it were a wooden stock, because it contains in itself a multitude of books, as it were of branches."

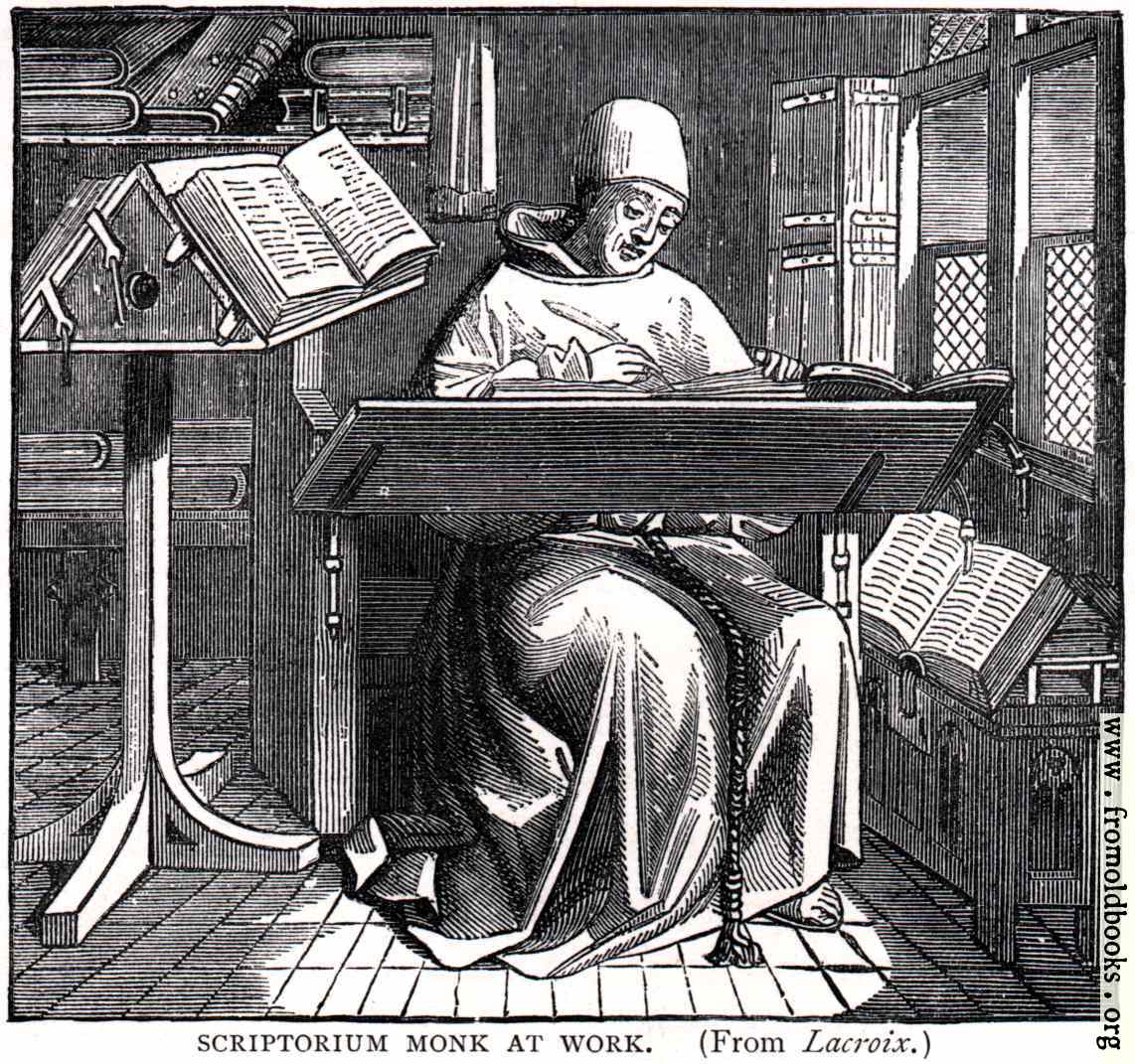

Middle Ages

Manuscripts

The fall of the Roman Empire in the fifth century A.D. saw the decline of the culture of ancient Rome. Papyrus became difficult to obtain, due to lack of contact with Egypt, and parchment, which had been used for centuries, began to be the main writing material.

Monasteries carried on the Latin writing tradition in the Western Roman Empire. Cassiodorus, in the monastery of Vivarium (established around 540), stressed the importance of copying texts.[12] St. Benedict of Nursia, in his Regula Monachorum (completed around the middle of the 6th century) later also promoted reading.[13] The Rule of St. Benedict (Ch. XLVIII), which set aside certain times for reading, greatly influenced the monastic culture of the Middle Ages, and is one of the reasons why the clergy were the predominant readers of books. The tradition and style of the Roman Empire still dominated, but slowly the peculiar medieval book culture emerged.

Before the invention and adoption of the printing press, almost all books were copied by hand, making books expensive and comparatively rare. Smaller monasteries usually had only some dozen books, medium sized perhaps a couple hundred. By the ninth century, larger collections held around 500 volumes; and even at the end of the Middle Ages, the papal library in Avignon and Paris library of Sorbonne held only around 2,000 volumes.[14]

The scriptorium of the monastery was usually located over the chapter house. Artificial light was forbidden, for fear it may damage the manuscripts. There were five types of scribes:

- Calligraphers, who dealt in fine book production

- Copyists, who dealt with basic production and correspondence

- Correctors, who collated and compared a finished book with the manuscript from which it had been produced

- Illuminators, who painted illustrations

- Rubricators, who painted in the red letters

The bookmaking process was long and laborious. The parchment had to be prepared, then the unbound pages were planned and ruled with a blunt tool or lead, after which the text was written by the scribe, who usually left blank areas for illustration and rubrication. Finally the book was bound by the bookbinder.[15]

Different types of ink were known in antiquity, usually prepared from soot and gum, and later also from gall nuts and iron vitriol. This gave writing the typical brownish black color, but black or brown were not the only colors used. There are texts written in red or even gold, and different colors were used for illumination. Sometimes the whole parchment was colored purple, and the text was written on it with gold or silver (eg Codex Argenteus).[16]

Irish monks introduced spacing between words in the seventh century. This facilitated reading, as these monks tended to be less familiar with Latin. However the use of spaces between words did not become commonplace before the 12th century. It has been argued,[17] that the use of spacing between words shows the transition from semi-vocalized reading into silent reading.

The first books used parchment or vellum (calf skin) for the pages. The book covers were made of wood and covered with leather. As dried parchment tends to assume the form before processing, the books were fitted with clasps or straps. During the later Middle Ages, when public libraries appeared, books were often chained to a bookshelf or a desk to prevent theft. The so called libri catenati were used up to 18th century.

At first books were copied mostly in monasteries, one at a time. With the rise of universities in the 13th century, the Manuscript culture of the time lead to an increase in the demand for books, and a new system for copying books appeared. The books were divided into unbound leaves (pecia), which were lent out to different copyists, so the speed of book production was considerably increased. The system was maintained by stationers guilds, which were secular, and produced both religious and non-religious material.[18]

Judaism has kept the art of the scribe alive up to the present. According to Jewish tradition, the Torah scroll placed in a synagogue must be written by hand on parchment, and a printed book would not do (though the congregation may use printed prayer books, and printed copies of the Scriptures are used for study outside the synagoguge). A sofer (scribe) is a highly respected member of any observant Jewish community.

Wood block printing

In woodblock printing, a relief image of an entire page was carved into blocks of wood, inked, and used to print copies of that page. This method originated in China, in the Han dynasty (before 220AD), as a method of printing on textiles and later paper, and was widely used throughout East Asia. The oldest dated book printed by this method is The Diamond Sutra (868 AD).

The method (called Woodcut when used in art) arrived in Europe in the early 14th century. Books (known as block-books), as well as playing-cards and religious pictures, began to be produced by this method. Creating an entire book was a painstaking process, requiring a hand-carved block for each page; and the wood blocks tended to crack, if stored for long.

Movable type and incunabula

The Chinese inventor Pi Sheng made movable type of earthenware circa 1045, but there are no known surviving examples of his printing. Metal movable type was invented in Korea during the Goryeo Dynasty (around 1230), but was not widely used: one reason being the enormous Chinese character set. Around 1450, in what is commonly regarded as an independent invention, Johannes Gutenberg invented movable type in Europe, along with innovations in casting the type based on a matrix and hand mould. This invention gradually made books less expensive to produce, and more widely available.

Early printed books, single sheets and images which were created before the year 1501 in Europe are known as incunabula. A man born in 1453, the year of the fall of Constantinople, could look back from his fiftieth year on a lifetime in which about eight million books had been printed, more perhaps than all the scribes of Europe had produced since Constantine founded his city in A.D. 330.[19]

Modern world

Steam-powered printing presses became popular in the early 1800s. These machines could print 1,100 sheets per hour, but workers could only set 2,000 letters per hour.

Monotype and linotype presses were introduced in the late 19th century. They could set more than 6,000 letters per hour and an entire line of type at once.

The centuries after the 15th century were thus spent on improving both the printing press and the conditions for freedom of the press through the gradual relaxation of restrictive censorship laws. See also intellectual property, public domain, copyright. In mid-20th century, Europe book production had risen to over 200,000 titles per year.

Book manufacturing in the modern world

The methods used for the printing and binding of books continued fundamentally unchanged from the 15th century into the early years of the 20th century. While there was of course more mechanization, Gutenberg would have had no difficulty in understanding what was going on if he had visited a book printer in 1900.

Gutenberg’s “invention” was the use of movable metal types, assembled into words, lines, and pages and then printed by letterpress. In letterpress printing ink is spread onto the tops of raised metal type, and is transferred onto a sheet of paper which is pressed against the type. Sheet-fed letterpress printing is still available but tends to be used for collector’s books and is now more of an art form than a commercial technique. [see Letterpress]

Today most books are printed by offset lithography in which an image of the material to be printed is photographically or digitally transferred to a flexible metal plate where it is developed to exploit the antipathy between grease (the ink) and water. When the plate is mounted on the press, water is spread over it. The developed areas of the plate repel water thus allowing the ink to adhere to only those parts of the plate which are to print. The ink is then offset onto a rubbery blanket (to avoid all that water soaking the paper) and then finally to the paper. [see Lithography]

When a book is printed the pages are laid out on the plate so that after the printed sheet is folded the pages will be in the correct sequence. [see Imposition] Books tend to be manufactured nowadays in a few standard sizes. The sizes of books are usually specified as “trim size”: the size of the page after the sheet has been folded and trimmed. Trimming involves cutting approximately 1/8” off top, bottom and fore-edge (the edge opposite to the spine) as part of the binding process in order to remove the folds so that the pages can be opened. The standard sizes result from sheet sizes (therefore machine sizes) which became popular 200 or 300 years ago, and have come to dominate the industry. The basic standard commercial book sizes in America, always expressed as width x height in USA; some examples are: 4-1/4” x 7” (rack size paperback) 5-1/8” x 7-5/8” (digest size paperback) 5-1/2” x 8-1/4” 5-1/2” x 8-1/2” 6-1/8” x 9-1/4” 7” x 10” 8-1/2” x 11”. These “standard” trim sizes will often vary slightly depending on the particular printing presses used, and on the imprecision of the trimming operation. Of course other trim sizes are available, and some publishers favor sizes not listed here which they might nominate as “standard” as well, such as 6” x 9”, 8” x 10”. In Britain the equivalent standard sizes differ slightly, as well as now being expressed in millimeters, and with height preceding width. Thus the UK equivalent of 6-1/8” x 9-1/4” is 234 x 156mm. British conventions in this regard prevail throughout the English speaking world, except for USA. The European book manufacturing industry works to a completely different set of standards.

Some books, particularly those with shorter runs (i.e. of which fewer copies are to be made) will be printed on sheet-fed offset presses, but most books are now printed on web presses, which are fed by a continuous roll of paper, and can consequently print more copies in a shorter time. On a sheet-fed press a stack of sheets of paper stands at one end of the press, and each sheet passes through the press individually. The paper will be printed on both sides and delivered, flat, as a stack of paper at the other end of the press. These sheets then have to be folded on another machine which uses bars, rollers and cutters to fold the sheet up into one or more signatures. A signature is a section of a book, usually of 32 pages, but sometimes 16, 48 or even 64 pages. After the signatures are all folded they are gathered: placed in sequence in bins over a circulating belt onto which one signature from each bin is dropped. Thus as the line circulates a complete “book” is collected together in one stack, next to another, and another.

A web press carries out the folding itself, delivering bundles of signatures ready to go into the gathering line. Notice that when the book is being printed it is being printed one (or two) signatures at a time, not one complete book at a time. Thus if there are to be 10,000 copies printed, the press will run 10,000 of the first form (the pages imaged onto the first plate and its back-up plate, representing one or two signatures), then 10,000 of the next form, and so on till all the signatures have been printed. Actually, because there is a known average spoilage rate in each of the steps in the book’s progress through the manufacturing system, if 10,000 books are to be made, the printer will print between 10,500 and 11,000 copies so that subsequent spoilage will still allow the delivery of the ordered quantity of books. Sources of spoilage tend to be mainly make-readies.

A make-ready is the preparatory work carried out by the pressmen to get the printing press up to the required quality of impression. Included in make-ready is the time taken to mount the plate onto the machine, clean up any mess from the previous job, and get the press up to speed. The main part of making-ready is however getting the ink/water balance right, and ensuring that the inking is even across the whole width of the paper. This is done by running paper through the press and printing waste pages while adjusting the press to improve quality. Desitometers are used to ensure even inking and consistency from one form to another. As soon as the pressman decides that the printing is correct, all the make-ready sheets will be discarded, and the press will start making books. Similar make readies take place in the folding and binding areas, each involving spoilage of paper.

After the signatures are folded and gathered, they move into the bindery. In the middle of the last century there were still many trade binders – stand-alone binding companies which did no printing, specializing in binding alone. At that time, largely because of the dominance of letterpress printing, the pattern of the industry was for typesetting and printing to take place in one location, and binding in a different factory. When type was all metal, a typical book’s worth of type would be bulky, fragile and heavy. The less it was moved in this condition the better: so it was almost invariable that printing would be carried out in the same location as the typesetting. Printed sheets on the other hand could easily be moved. Now, because of the increasing computerization of the process of preparing a book for the printer, the typesetting part of the job has flowed upstream, where it is done either by separately contracting companies working for the publisher, by the publishers themselves, or even by the authors. Mergers in the book manufacturing industry mean that it is now unusual to find a bindery which is not also involved in book printing (and vice versa).

If the book is a hardback its path through the bindery will involve more points of activity than if it is a paperback. A paperback binding line (a number of pieces of machinery linked by conveyor belts) involves few steps. The gathered signatures, book blocks, will be fed into the line where they will one by one be gripped by plates converging from each side of the book, turned spine up and advanced towards a gluing station. En route the spine of the book block will be ground off leaving a roughened edge to the tightly gripped collection of pages. The grinding leaves fibers which will grip onto the glue which is then spread onto the spine of the book. Covers then meet up with the book blocks, and one cover is dropped onto the glued spine of each book block, and is pressed against the spine by rollers. The book is then carried forward to the trimming station, where a three-knife trimmer will simultaneously cut the top and bottom and the fore-edge of the paperback to leave clear square edges. The books are then packed into cartons, or packed on skids, and shipped.

Binding a hardback is more complicated. Look at a hardback book and you will see the cover overlaps the pages by about 1/8” all round. These overlaps are called squares. The blank piece of paper inside the cover is called the endpaper, or endsheet: it is of somewhat stronger paper than the rest of the book as it is the endpapers that hold the book into the case. The endpapers will be tipped to the first and last signatures before the separate signatures are placed into the bins on the gathering line. Tipping involves spreading some glue along the spine edge of the folded endpaper and pressing the endpaper against the signature. The gathered signatures are then glued along the spine, and the book block is trimmed, like the paperback, but will continue after this to the rounder and backer. The book block together with its endpapers will be gripped from the sides and passed under a roller with presses it from side to side, smashing the spine down and out around the sides so that the entire book takes on a rounded cross section: convex on the spine, concave at the fore-edge, with “ears” projecting on either side of the spine. Then the spine is glued again, a paper liner is stuck to it and headbands and footbands are applied. Next a crash lining (an open weave cloth somewhat like a stronger cheesecloth) is usually applied, overlapping the sides of the spine by an inch or more. Finally the inside of the case, which has been constructed and foil-stamped off-line on a separate machine, is glued on either side (but not on the spine area) and placed over the book block. This entire sandwich is now gripped from the outside and pressed together to form a solid bond between the endpapers and the inside of the case. The crash lining, which is glued to the spine of the pages, but not the spine of the case, is held between the endpapers and the case sides, and in fact provides most of the strength holding the book block into the case. The book will then be jacketed (most often by hand, allowing this stage to be an inspection stage also) before being packed ready for shipment.

The sequence of events can vary slightly, and usually the entire sequence does not occur in one continuous pass through a binding line. What has been described above is unsewn binding, now increasingly common. The signatures of a book can also be held together by Smyth sewing. Needles pass through the spine fold of each signature in succession, from the outside to the center of the fold, sewing the pages of the signature together and each signature to its neighbors. McCain sewing, often used in schoolbook binding, involves drilling holes through the entire book and sewing through all the pages from front to back near the spine edge. Both of these methods mean that the folds in the spine of the book will not be ground off in the binding line. This is true of another technique, notch binding, where gashes about an inch long are made at intervals through the fold in the spine of each signature, parallel to the spine direction. In the binding line glue is forced into these “notches” right to the center of the signature, so that every pair of pages in the signature is bonded to every other one, just as in the Smyth sewn book. The rest of the binding process is similar in all instances. Sewn and notch bound books can be bound as either hardbacks or paperbacks.

Making cases happens off-line and prior to the book’s arrival at the binding line. In the most basic case making, two pieces of cardboard are placed onto a glued piece of cloth with a space between them into which is glued a thinner board cut to the width of the spine of the book. The overlapping edges of the cloth (about 5/8” all round) are folded over the boards, and pressed down to adhere. After case making the stack of cases will go to the foil stamping area. Metal dies, photoengraved elsewhere, are mounted in the stamping machine and rolls of foil are positioned to pass between the dies and the case to be stamped. Heat and pressure cause the foil to detach from its backing and adhere to the case. Foils come in various shades of gold and silver and in a variety pigment colors, and by careful setup quite elaborate effects can be achieved by using different rolls of foil on the one book. Cases can also be made from paper which has been printed separately and then protected with clear film lamination. A three-piece case is made similarly but has a different material on the spine and overlapping onto the sides: so it starts out as three pieces of material, one each of a cheaper material for the sides and the different, stronger material for the spine.

Recent developments in book manufacturing include the development of digital printing. Book pages are printed, in much the same way as an office copier works, using toner rather than ink. Each book is printed in one pass, not as separate signatures. Digital printing has permitted the manufacture of much smaller quantities than offset, in part because of the absence of make readies and of spoilage. One might think of a web press as printing quantities over 2000, quantities from 250 to 2000 being printed on sheet-fed presses, and digital presses doing quantities below 250. These numbers are of course only approximate and will vary from supplier to supplier, and from book to book depending on its characteristics. Digital printing has opened up the possibility of print-on-demand, where no books are printed until after an order is received from a customer. That books can be economically printed in an edition of one copy is truly a development that would surprise Mr. Gutenberg.

Transition to digital format

The term e-book is a contraction of "electronic book"; it refers to a digital version of a conventional print book. An e-book is usually made available through the internet, but also on CD-ROM and other forms. E-Books are read by means of a physical book display device known as an e-book reader, such as the Sony Reader or the Amazon Kindle. These devices attempt to mimic the experience of reading a print book.

Throughout the 20th century, libraries have faced an ever-increasing rate of publishing, sometimes called an information explosion. The advent of electronic publishing and the Internet means that much new information is not printed in paper books, but is made available online through a digital library, on CD-ROM, or in the form of e-books. An on-line book is an e-book that is available online through the internet.

Though many books are produced digitally, most digital versions are not available to the public, and there is no decline in the rate of paper publishing[citation needed]. There is an effort, however, to convert books that are in the public domain into a digital medium for unlimited redistribution and infinite availability. This effort is spearheaded by Project Gutenberg combined with Distributed Proofreaders.

There have also been new developments in the process of publishing books. Technologies such as print on demand, which make it possible to print as few as one book at a time, have made self-publishing much easier and more affordable. On-demand publishing has allowed publishers, by avoiding the high costs of warehousing, to keep low-selling books in print rather than declaring them out of print.

Source: Wikipedia

No comments:

Post a Comment